November 2022 Invasive Plant of the Month

SICIM Email

Nonnative Wisteria:

Sweet Chinese Wisteria, Wisteria sinensis (Sims.) DC, Japanese Wisteria, Wisteria floribunda (Willd.) DC, and Silky Wisteria, Wisteria venusta (Rehd. & Wils)

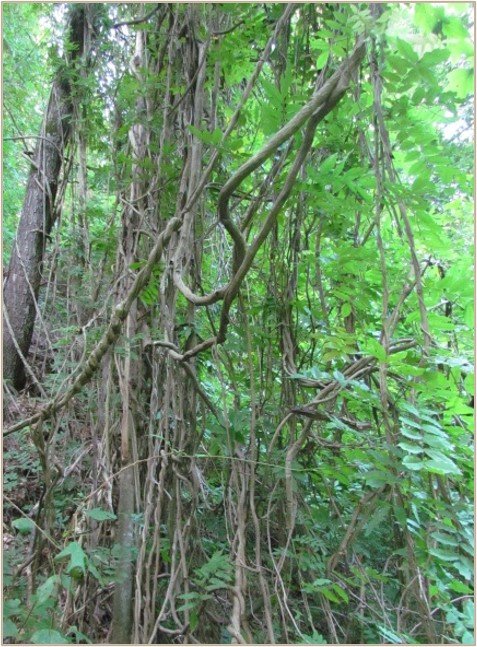

Wisterias are a popular landscape perennial vine due to their stunning, often fragrant (Japanese and Sweet Chinese wisterias), white, purple and blue-violet flowers. They have been planted due to their attractive looks, but they are invasive, which means they cause harm when grown in areas they are not native to. American Wisteria (Wisteria frutescens) is an excellent alternative to the invasive nonnative ones. Three nonnative wisterias native to Asia (note Sweet Chinese and Japanese denote their native ranges) are often sold and used in landscapes. They were introduced to North American beginning in the 1800’s as ornamentals. Both Sweet Chinese and Japanese wisterias have been grown as decorative additions to porches, walls, gardens, gazebos, etc. There are many cultivars of all three species and Japanese and Sweet Chinese wisterias hybridize with each other. Wisterias are a member of the pea family, Fabaceae, and are vigorous woody vines that can reach lengths of 70 feet long or as long as the tree they are climbing and be 15 inches in diameter on older plants. They create dense infestations that topple trees and densely cover the ground with running vines.

IDENTIFICATION & BIOLOGY: Leaves: Leaves of wisterias are alternate and compound consisting of 7-13 (Chinese), 13-19 (Japanese), and 9-13 (Silky) ovate-oblong to ovate-elliptic leaflets with stalks that have swollen bases and tapering leaf tips. They are green and hairless at maturity but densely hairy when young. Leaf margins are entire and wavy. Stems: Wisteria vine stems are somewhat smooth. Vine color varies from grey-brown to tan (Chinese) to whitish (Japanese). Stems can grow up to 10 feet per growing season. Flowers: Flowers range from white (Silky) to purple, violet-blue (Japanese), to blue and blue-violet (Chinese). Cultivar colors vary. They are arranged in 6-12-inch-long dangling racemes packed with one-half to one-inch flowers. Nonnative wisterias can take up to 15 years to flower. Flowering begins in late March and continues through May. Sweet Chinese wisteria flowers open all at once while Japanese wisteria flowers open from the back to the front. All three nonnative wisteria species open before the leaves fully develop. Fruits: Fruits are 4-6-inch-long velutinous pods that contain one to eight flat, round, brown seeds with constrictions between each seed (Photograph 4) that develop July through November. The greenish brown to golden colored seed pods often remain on the vine throughout fall and winter. The vines of Sweet Chinese Wisteria twine counterclockwise, while the vines of Japanese Wisteria twine clockwise. There are at least 18 cultivars of Sweet Chinese wisteria and many of Japanese wisteria. Sweet Chinese Wisteria hybridizes with Japanese wisteria (W. x formosa). Spread: These long-lived species reproduce primarily by vegetative means via numerous stolons that develop roots and shoots at short intervals.

LOOK-A-LIKES: The native American wisteria (W. frutescens) may be confused with nonnative wisterias. American wisteria is less aggressive, occurs in wet forests and edges, and matures sooner whereas nonnative wisterias can take years to flower. American wisteria flowers after the leaves develop and later in the growing season (June through August). Overall, American wisteria flowers are shorter and rounder and more compact compared to the longer pendulous blossoms of the nonnative wisterias. American wisteria is also less aromatic than Sweet Chinese or Japanese wisteria. The long, twisted seed pod of American wisteria is smooth or not as hairy compared to the very velvety, shorter and untwisted pods of the nonnative wisterias.

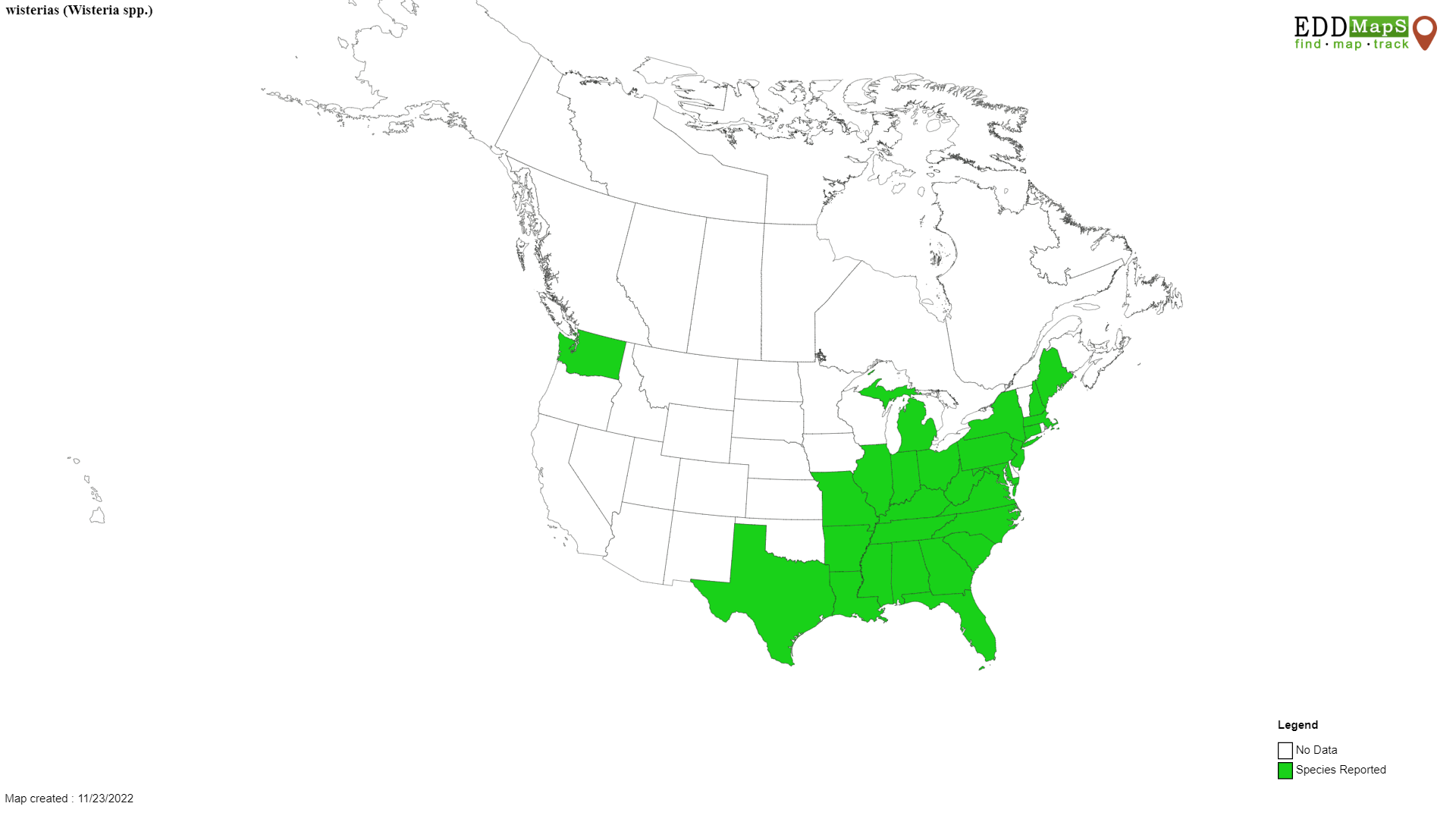

HABITAT & DISTRIBUTION: Infestations are frequently found escaped from homesites where it invades forests and forest edges. The ideal habitat is full sun, but it will persist in partial shade. It grows on wet to dry sites and colonizes by vines twining and covering shrubs and trees and by runner rooting at nodes when vines cover leaf litter. It topples trees and creates sunny openings that favor aggressive growth. Seeds are large and therefore dispersed by water instead of animals. These nonnative, invasive wisterias are found extensively throughout the eastern United States. Infestations have been reported from New York to Florida, west to the Great Lakes states south to Arkansas and Texas. Infestations have also been reported in Washington state (Figure 1).

ECOLOGICAL THREAT: Wisteria species can live 50 to 100 years, girdling and crushing trees and structures with its weight. The vine spreads by rooting at each node and through stolons (above ground stems) that develop roots and shoots at short intervals, creating dense infestations. Wisterias are toxic to humans and pets. It can overtop, shade out, weigh down, and break woody structures, as well as shrubs and trees. Wisteria infestations reduce native plant species diversity and disrupt wildlife habitat.

CONTROL: Efforts should be made to educate natural resource professionals and landowners on nonnative wisteria identification to improve early detection and control. Where it already occurs, control should be conducted before it produces seed in mid-to late June. Existing populations are most effectively controlled with post-emergent herbicide before fruit sets in summer. Control efforts and monitoring should continue until no wisteria plants remain.

Prevention: Avoid using nonnative wisteria species in landscaped areas.

Mechanical: This is only recommended for small vines, or in sensitive areas where chemical herbicide should not be used. This is labor-intensive and requires constant mowing all season to prevent the vine from developing flowers and seeds and exhaust the plant. This is likely to take more than one growing season.

Biological: There are no known biological control methods for nonnative wisteria at this time.

Chemical: Large infestations or vines can be controlled with a cut stem treatment. In the spring or summer, when the vine is actively growing, cut it close to ground level as near to the root collar as possible and immediately brush the cut surface with a systemic herbicide concentrate of 20% such as a glyphosate containing product. Use a foliar application and spray new sprouts with a 2% concentrate broadleaf herbicide, taking care to avoid spraying on surrounding nontarget plants. Repeat as necessary on new sprouts. Use foliar spray herbicide treatments to control large infestations while also treating large vines with cut stem method. Repeated burning will not control wisteria infestations.

Nonnative wisterias are vigorous growers. It will take repeated treatments, along with annual monitoring for many years to control and eradicate populations. The sheer volume of biomass within these infestations can take several growing seasons to rot. Cut vines that are left around trees will resprout and continue to girdle a tree if not treated repeatedly during a growing season or removed completely.

To report an invasive species that is invading natural areas, use Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS): https://www.eddmaps.org/report/

IMPORTANT: The pesticide label is the law! When using any chemical control, always read the entire pesticide label carefully, follow all mixing and application instructions and use all personal protective gear and clothing specified. Contact the Office of Indiana State Chemist (OISC) for additional pesticide use requirements, restrictions, or recommendations. SICIM does not endorse any specific pesticide brand.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

Invasive.org: Chinese wisteria, Wisteria sinensis Fabales: Fabaceae (invasive.org)

Penn State Invasive Plant Species Management: ISM_QS_9_Woody Vines.pdf

Purdue University Extension Invasive Plant Series:

Plant Conservation Alliance’s Alien Plant Working Group:

USDA Forest Service. Weed of the Week: Microsoft Word - Exotic wisterias.doc (invasive.org)

REFERENCES:

Gleason, H. A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. Second Edition. The New York Botanical Garden.

EDDMapS. 2022. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed November 28, 2022.

Miller, James H., E. B. Chambliss and N. J. Loewenstein. 2012. A Field Guide for the Identification of Invasive Plants in Southern Forests.

Miller, James H., S. T. Manning and S. R. Enloe. 2010. A Management Guide for Invasive Plants in Southern Forests.

Plant Conservation Alliance. 2005. Fact Sheet: Exotic Wisterias. Accessed November 21, 2022: file:///D:/III/Invasive%20Species%20Work/Invasive%20Species/Specific%20Species/Wisteria/exoticwisterias.pdf